Nancy Flanagan: ‘Self-Care’ vs. Sustainable Leadership

Nancy Flanagan takes a look at the challenges of teacher leadership. Reposted with permission.

I once was on a panel at a Governors Summit on Education in Michigan. The topic was ‘teacher leadership.’ It was the usual format—each panelist gets a pre-determined number of minutes to pontificate (which they invariably overrun)—and then (theoretically) there is open discussion among the panelists, and questions from the audience. The line-up was: A state legislator, a representative from one of Michigan’s two teacher unions, and me.

I was the first speaker and started with the premise—copped from Roland Barth—that if all students can learn, then all teachers can lead. I fleshed that idea out, a bit—that practicing teachers need a voice at the policy-making table, that teachers’ control over their own professional work would enhance their practice and enthusiasm for teaching, as well as their efficacy. And so on.

Legislator was the second speaker and he strongly disagreed. He asserted that his role, over so-called teacher leadership, was oversight. Teachers are public employees who need to be kept on a tight rein; their work rigorously evaluated. If they want to lead, they can lead their second-graders out to the playground for recess (audience laughs). He and his colleagues were the rule-makers and goal setters, not teachers.

Then the union guy spoke. And he, too, felt that ‘all teachers can lead’ was a falsehood. Teachers had no business sticking their nose into policy. That was the union’s job. And it was an administrators’ job to lead a district or building—and suffer the consequences of failure. He knew plenty of teachers who were excellent classroom practitioners but didn’t have the skills, desire or moxie to lead. If they wanted to lead, they should run for a position in their union, or get administrative certification. Applause.

Because the Summit was on a weekday, the hundreds of people sitting in the ballroom were mostly legislators or their staffers, heavily from the Governor’s party, plus university and Department of Ed folks, and reporters. Not teachers.

Although I enjoyed a delicious, expensive banquet lunch afterward, I met nobody whose thinking was aligned with mine, re: organic teacher leadership.

Not a great experience. But telling.

Now, many years later, I still believe that experienced teachers want to lead, and are well-positioned to inform the conversation around education policy.

In fact, I think a lot of what happened to Democrats in Virginia—in a race they should have won handily—had to do with suppressing the threat of genuine teacher voices around what gets taught in real classrooms, maybe taking down public education in the process. Plus the utter disruption of a pandemic–and racism, of course.

Teachers are under siege. It’s not surprising that free-floating angst, generated by a highly disruptive pandemic, has been aimed at public schools. It happens cyclically—everything from rising pregnancy rates to chronic illiteracy in poverty-ridden neighborhoods is blamed on educators.

Because–you know what’s coming–everyone went to school and thinks they understand schooling. A pandemic that shuts the entire system down, however, is exponentially catastrophic, impacting everyone. Anger at public schools, even for made-up reasons, is inevitable. It’s the nearest target.

For the last century or so, teachers have been an increasingly female workforce, seriously underpaid and subject to increasingly rigid control from government and on-site leadership. Pretty much the model my co-panelists understood and defended: Some of us make the decisions, others do the work. And hey—enjoy your summers!

But it’s a relatively young and inexperienced teacher workforce now, and the frightening stories about teachers leaving, in droves, with nobody to replace them, ought to force the education community to ask themselves: What would keep the EXPERIENCED TEACHERS WE ALREADY HAVE (sorry) in the classroom for a couple more years, until we rebuild a leaky pipeline?

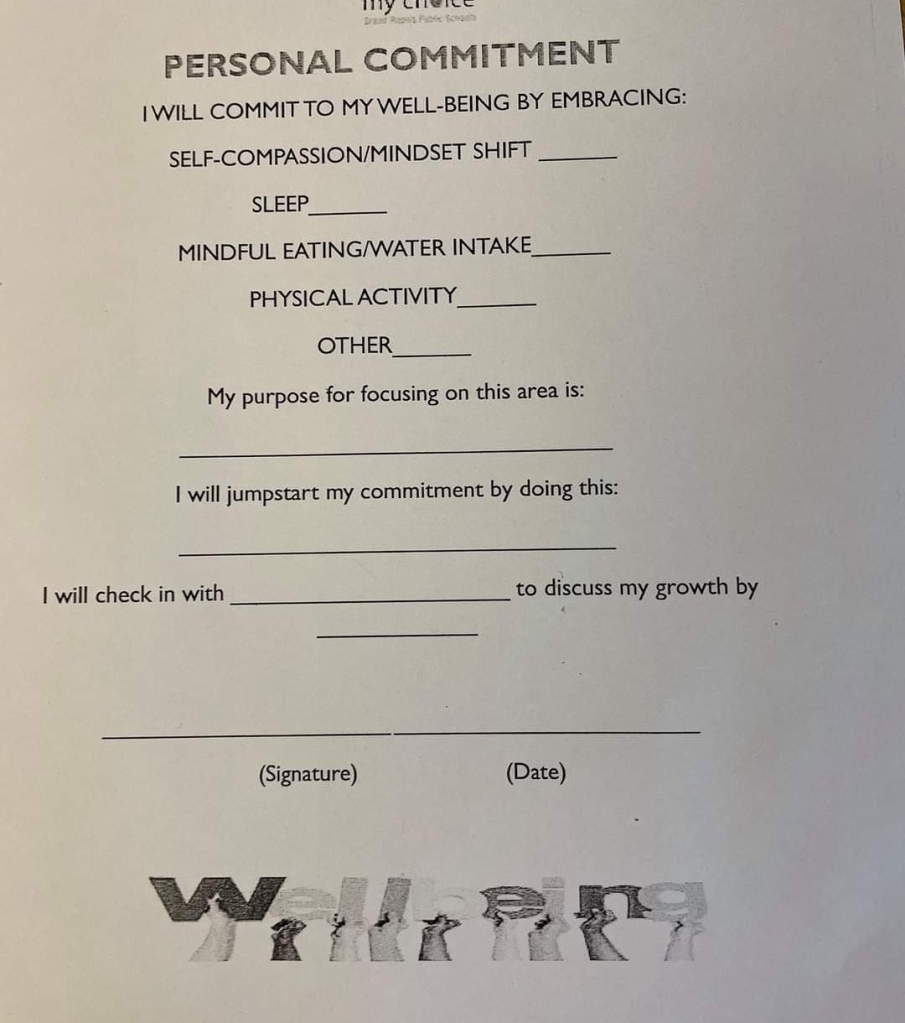

Well, it isn’t the ‘Wellbeing’ worksheet (see photo, below), which feels like one of those make-work reproducible masters teachers used to pull out on a sub day. Self-care dittos.

Here—fill this out. Feel better! Clearly, whoever designed this worksheet does not understand the relationship between drinking more water and the one three-minute window per day when peeing is possible.

Look, I understand that there’s no easy remedy for the conditions teachers are working under: Angry parents. Lies about the curriculum. Anti-vaxxer moms and virus daredevils. What could a school leader who really wanted to support her staff do?

Grow a backbone. Support public education. Here’s a list of 14 viable suggestions for doing that.

Hiring the best possible people, paying them fairly, giving them time to work collaboratively, honoring their expertise, and releasing their creativity? How does that sound as a recipe for school-based self-care?

What do teachers want? What all professionals want: Autonomy. Mastery. Purpose.